In our first discussion of one book among the slew of books written to help us plebes decipher James Joyce, we looked at James Joyce’s Ulysses and Anthony Burgess’s Rejoyce (1965). (Anthony Burgess who is best known for his 1962 novel, A Clockwork Orange.)

Part Two will find us taking on Joyce’s last novel, Finnegans Wake, and John Bishop’s 1986 tome, Joyce’s Book of the Dark.

If you weren't aware already, Finnegan's Wake is one of the most incredibly written and misunderstood books ever printed. It’s hard to even find an entry point in beginning to talk about it, not least of all because the book has no concrete entry point of its own but starts in the middle of a sentence. Joyce drops his readers into his ocean of words and we’re swept away by the fast moving and often baffling current. Here’s what I mean:

“But the duvlin sulph was in Glugger, that lost-to-lurning. Punct. He was sbuffing and sputing, tussing like anisine, whipping his eyesoult and gnatsching his teats over the brividies from existers and the outher liubbocks of life. He halth kelchy chosen a clayblade and makes prayses to his three of clubs. To part from these, my corsets, is into overlusting fear. Acts of feet, hoof and jarrety: athletes longfoot. Djowl, uphere!”

But then, what does one expect? Driven mad by the trials and tribulations of Ulysses (the struggle to complete it and then the obscenity trial(s) shortly after its original publication) as well as his ongoing battle with eye problems (iritis, glaucoma and cataracts leading to twenty operations and unimaginable pain and suffering), it’s a wonder he even bothered with another novel -- let alone one of such far-reaching magnitude. The popular notion is that Ulysses is a book about and which takes place in a single day and Finnegans Wake being about “night,” specifically dreams and the netherworld of anything-goes. But that theory, even if it’s what the author had in mind as a concept, is just too easy of a description.

Hardly anyone understood what Joyce had written. Even those who stood behind him years before while he toiled arduously on Ulysses thought he’d gone off the rails. “I am made in such a way that I do not care much for the output from your Wholesale Safety Pun Factory,” wrote Harriet Weaver to Joyce in a twisted fan letter, “nor for the darknesses and unintelligibilities of your deliberately entangled language system. It seems to me you are wasting your genius.”

D.H. Lawrence didn’t seem to enjoy the ride, either: “My God, what a clumsy olla putrida James Joyce is! Nothing but old fags and cabbage-stumps of quotations from the Bible and the rest, stewed in the juice of deliberate journalistic dirty-mindedness – what old and hard-worked staleness, masquerading as the all-new!” Ever the competitor, Vladimir Nabokov didn’t want Lawrence to get all the fun and so did his own act of bitchiness by whining the book was, “nothing but a formless and dull mass of phony folklore, a cold pudding of a book, a persistent snore in the next room [...] and only the infrequent snatches of heavenly intonations redeem it from utter insipidity…” Yowza!

Two editors at Houyhnhnm Press, Danise Rose and John O’Hanlon, set out to publish a “more comprehensible” version of the book and, after thirty goddamn years of work, it was finally published in 2010. To get an idea of the work involved, take a look at Rose’s personal copy of Wake with she made her own notations of possible amendments:

Naturally, a boundary smashing book as such attracts those overachieving souls who wish to decipher it all for the good of humanity. Sticking with the absurdity of it all, I set before you one such example: John Bishop’s 1986 tome, Joyce’s Book of the Dark. It is a 400+ mind-melting page the likes of which not seen since … well, since Finnegans Wake was published some forty-seven years previous. It’s hard to not hype the magnitude of Bishop’s work. A reviewer for the esteemed Library Journal went for the undersell approach by writing that it: “will help serious readers of the Wake get their bearings.” Yes, well maybe that’s true, but whatever bearings Bishop may help us find in Joyce’s work gets thrown off considerably by his own research. He atom-splits Wake into a trillion possibilities and connects the dots between the novel’s various influences: the political/philosophical teachings of Giocan Vico, the Egyptian Book Of The Dead, and that old stand-by reference point and all around great guy, Sigmund Freud. But that’s merely the beginning. In fact, that’s hardly the beginning. Let’s just take a gander at a random sentence, shall we:

“According to one line of speculation inevitably issuing from the Wake’s study of ‘meoptics,’ we might therefore conceive of an agent internal to the body agitating the ‘rods and cones of this even’s vision’ into wakefulness during visual dreams – and doing so not haphazardly, but with such weird precision as to etch there, graphically, people, scenes and even alphabetic characters of a sufficiently credulity-gripping lifelikeness as to conceive the dreamer of their reality.”

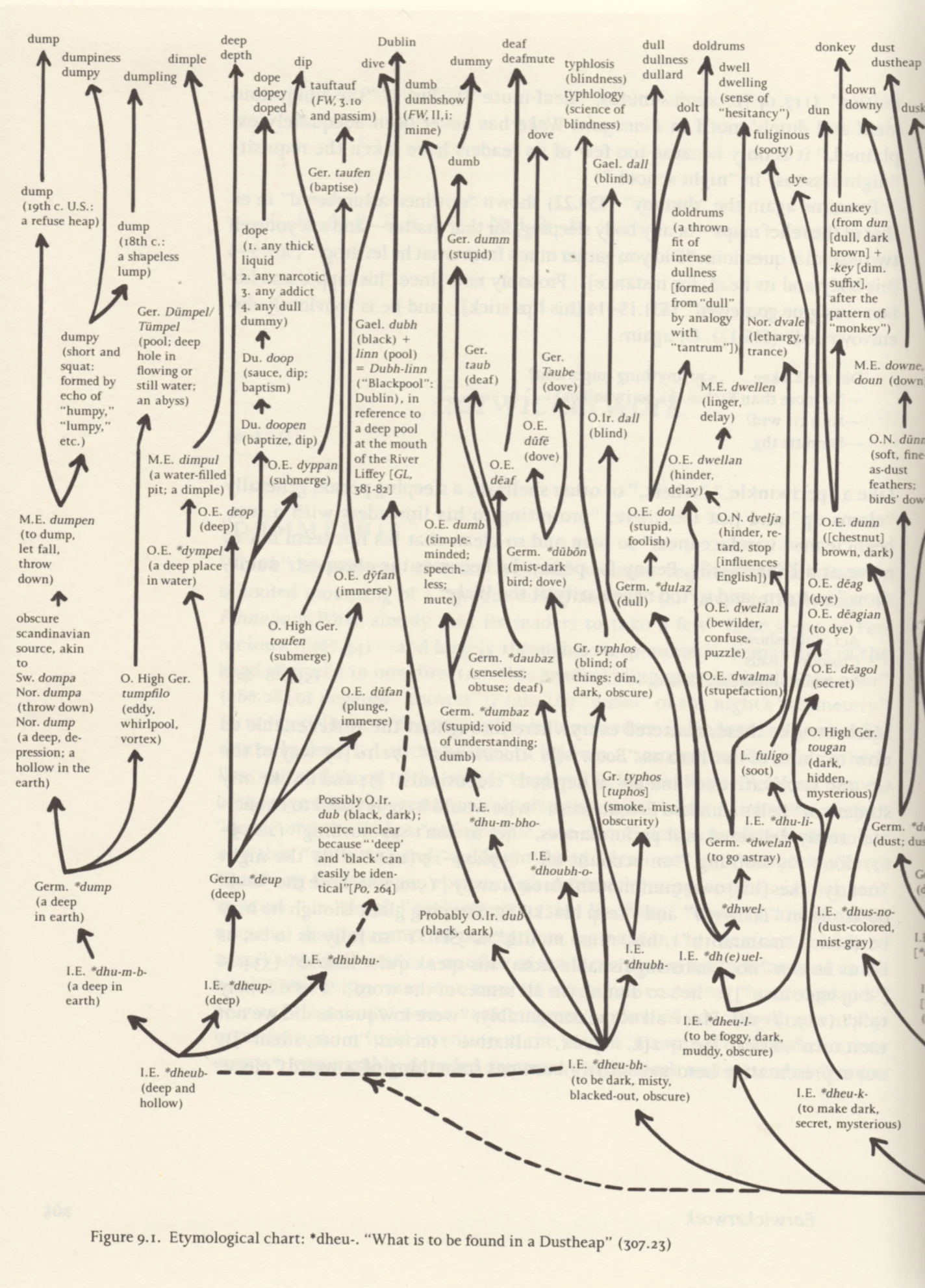

Yeah, that’s exactly what I was thinking! It’s not just words, either. Oh, no. He’s has gone to the trouble of making us some visual aids. Check this one out:

I’m not going to bother explaining that one for you (because I can’t). Here, try this one that is supposed to be a bit simpler:

Bishop is the sadist and we’re just masochists.

This book, like its subject matter, has the ability to induce panic attacks. The walls of the reader’s imagination are eliminated and the enormity of not just Finnegans Wake, but of the possibilities of the world and life itself, become almost too big for the mind to handle.

Expect to take this one slow. Bishop’s lofty ideas and theories require patience (Lord knows I haven’t read it all), but it’s worth the time and effort. In that way, Joyce’s Book of the Dark is perhaps the perfect companion to Finnegans Wake as both books challenge and reflect the wonders of language and thought.

However, an argument can be made that Bishop’s work is almost too much. Jeepers, maybe I don’t need a full breakdown of Egyptology in order to understand, say, three certain pages of this thing. (“That Joyce has in mind as a “premier terror” of the dark “errorland” of sleep, the loss of consciousness is suggested by the name that he repeatedly uses throughout the Wake to refer to the Egyptian afterworld.”) This is akin to getting your car stuck on a dirty, wet backroad only then watching the tow truck getting stuck in the same pit as it tries to pull it out.

Bishop himself is a professor of English at the University of California Berkeley, which means he’s about a mile from where I’m writing this thing so I could wander over to his office and ask him myself … but … I’m sure he’s busy.

Joyce’s Book of the Dark is a world unto itself: a fascinating verbal/visual gate-crashing study of the whole goddamn creative universe. It might someday get its own critical companion study -- one which helps us figure out what was going on in Bishop’s head, never mind Joyce’s. It creates new problems, new questions, new furrowed brows. If you want to get your hands really dirty and muck about in the essential fibers which make up the staggering brilliance of James Joyce, Book of the Dark is where you want to be.

But for those of us who need Joyce’s vision watered down just a wee bit more, there is another fantastic manual out there, one which even the hyper-kinetic American philosopher and psychonaut * Terrence McKenna endorsed some years ago. Stay tuned for part three.

*Yep, that’s an actual term, look it up.